Maritime Niche & Marine INdustry

Boh’s Experience, In-House Capabilities on Display at Ingram Site Marine-based commerce is huge in Louisiana.

Maritime Niche & Marine INdustry

Boh’s Experience, In-House Capabilities on Display at Ingram Site Marine-based commerce is huge in Louisiana.

In the last decade, traffic on the Mississippi River has risen steadily, with an average of 300 million short tons of product transported down the river each year, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Institute for Water Resources.

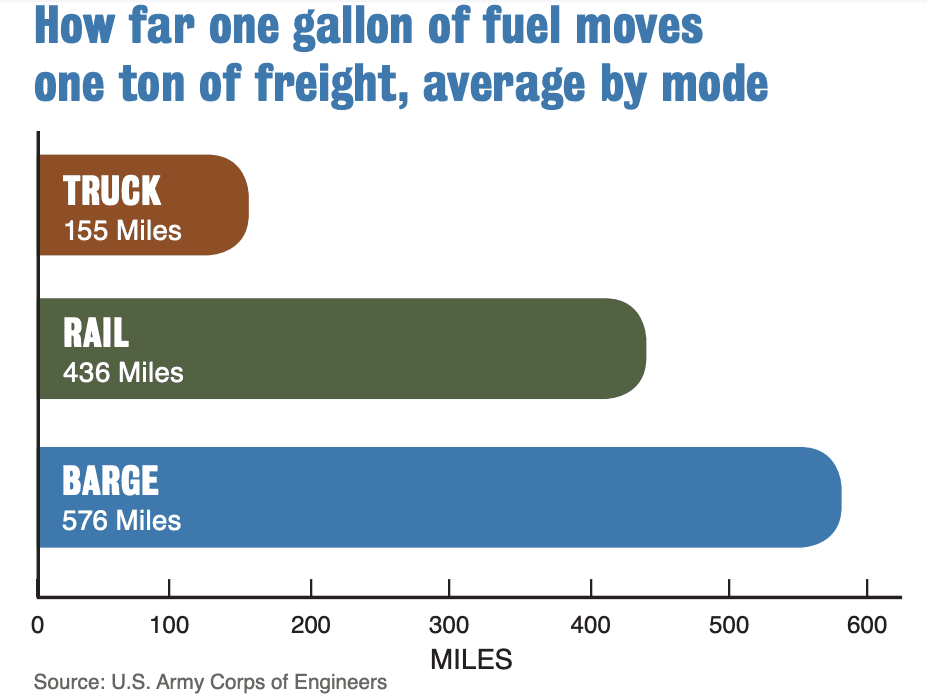

Much of that is barged in and out of south Louisiana ports, and consists mostly of crude oil, refined products, food and farm products. The economics of barging are hard to ignore—a single tug boat can move 36 barges at a time, the equivalent of 3,600 truckloads.

Few are as aware of the industry’s impact upon the state, or its close ties to construction, than Fred Fuchs, Boh’s Vice President of Piling and Marine. “I wouldn’t be surprised if, from 2000 until today, the volume of cargo in and around New Orleans has gone up 50%,” Fuchs said. With this increased volume, Fuchs has also seen a subsequent demand for the evolution of marine construction methods to enhance safety, reduce construction time, and improve efficiency.

For 60 years, Boh Bros. has been a major player in the construction of facilities to meet the growing demand for barge transportation. One of the more significant recent advancements has been a change from tripod structures to mono-pile mooring dolphins for fleeting pile design, which has significantly produced safer work environments, reduced construction time, and saved money. Use of the larger diameter piles has been made possible by the enhanced capabilities of cranes and pile hammers. “River conditions can be unpredictable, so you want to reduce the amount of time you’re out there,” Fuchs said.

In August, Boh began driving 18 monopiles to expand a mid-stream mooring facility, as well as to replace existing tripod dolphins, at Ingram Barge Group’s new Southern Regional Office in Reserve, La. David Sehrt, Ingram’s Senior Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, said the project will significantly augment its barge fleeting at the site.

“The work will add 56 parking spots for our barges,” Sehrt said. “The Reserve facility is a hub for us—when the barges come down from up north, they come down 30 to 40 at a time. We utilize the facility as a stopping off point, so we can redistribute the barges in ones, twos, fours, sixes, etc.” Ingram has been a marine transporter on America’s inland waterways since 1946, beginning as a small, family owned business and growing into the largest dry cargo carrier and one of the top chemical carriers on the river. The company operates a fleet of 140 towboats and 5,000 barges.

“One of the difficulties in establishing a fleet is that you need a significant amount of property, anywhere from 1,000 to 2,000 feet of riverfront, which is difficult to acquire along that particular stretch of the river,” he said. The Reserve facility is one of four operated by Ingram, with others in Port Allen, La., Columbus, Ky., and St. Louis, Mo.

Boh Taps into Unique Capabilities

After work began in August, the Ingram project quickly became a showcase of sorts for Boh. Grant Closson, project manager, said one of the primary challenges has been access—the Industrial Canal locks in New Orleans were undergoing a major renovation, so rather than making the short 5-mile journey from the fabrication yard into the Mississippi River, the piles had to travel an additional 250 miles to get to the site. Once the operation began full swing, Boh was transporting and driving about two piles per day.

“We’re driving 14 piles in a straight line to a depth of about 100 feet below the mudline so they can secure the spar barges in a fixed location,” Closson said. The spar barges are permanent fixtures at the mooring facility, attached to the dolphin by a steel yoke that rides up and down the pile.

Boh spliced the piles utilizing its submerged arc welding table at the Almonaster fabrication yard, following the steel’s 30-day journey from the supplier. Fuchs said the sub arc table has significantly enhanced Boh’s capabilities over the years, allowing it to fabricate the lengthy piles in-house. “Being able to fabricate these pieces ourselves provides value,” Fuchs added. “We can fit and weld those big diameter piles together in our own yard, giving us the ability to control the fabrication and painting so we can deliver our product more quickly to our customers.”

After delivery to the Ingram site, the monopiles were driven into place with a Manitowoc 4100 ringer crane and vibratory hammer. The 130-foot-long, 42-inch-diameter piles have a maximum wall thickness of 1.5 inches at the base. “Typically, the highest stress location is about 10 to 15 feet below the mud line, so that area needs to be the strongest,” Closson said.

As an additional challenge, the piles had to be driven through existing concrete mats, which had been previously placed on the river bottom by the Corps of Engineers to prevent erosion. “What the vibratory hammer can’t get through, we have an impact hammer as a backup,” he added. To repair the mats following the procedure, Boh placed limestone around each pile.

Closson said the process from there is fairly straightforward for a company with as much experience in marine construction as Boh—“We have our layout team on the levee shooting grades and telling us when to turn the hammer on and off. Once we get to grade, we disconnect from the pile.” A cap plate is welded to the top of each pile to create an airtight seal, thereby blocking moisture and preventing corrosion within the pipe. “We have to seal it off to kill the oxygen on the inside.”

Through it all, the Boh crew has been mindful of the heavy ship traffic along the river. As such, safety is a primary concern, so they practice a 100% lifejacket policy and have a rescue boat in the water at all times.

Lingo Unique to Marine Industry

While like a foreign language to some, words such as monopiles, spar barges and yokes are commonplace among those who work in the maritime industry.

For Fuchs and Closson, it’s part of their everyday language. It’s this knowledge of marine construction, gained from decades of experience in the Mississippi River, that differentiates Boh from its competitors. Additionally, unique capabilities such as in-house steel fabrication are complemented by an internal engineering staff.

“Our engineers help us design the means and methods of the project,” Closson said. “While the permanent material design is done by the owner’s engineer, we might see an opportunity for greater efficiencies that we can both design and fabricate. They give us a starting point, then we evaluate what would be the best and most efficient way to do it.”

While the ways and means of creating new maritime infrastructure have changed over the years, Ingram’s Sehrt said barges have changed surprisingly little. “What we’re building today are the same barges that were built 40 years ago,” he added. “We like them the same size because it makes it easier to redistribute the barges in different combinations. We’re also constrained by the size of the locks in the various riverways.”

Grain shipments comprise the bulk of Ingram’s Mississippi River traffic, with an expected 7,000 barge loads of grain coming into the Port of New Orleans in 2016. As such, the expanded capacity of the Reserve facility will enable the company to dock the barges as they arrive, then phase the deliveries to the port.

“We’ll be able to ship them in smaller quantities, since the ports don’t have the capacity to take 30 to 40 barges at once,” Sehrt said. He added that while this is his first experience using the monopiles for a mooring system, Ingram will likely use them again given the success of the project.

This article was originally published in The Boh Picture. To read about more of Boh’s projects, click here.