Night Shift: Boh Tweaks Causeway Crossover to Accelerate Schedule, Protect Public

About nine miles north of the Metairie shoreline, Boh Bros. recently completed a critical safety improvement to Lake Pontchartrain Causeway, while reducing cost and improvising schedule to make it happen.

For the most part, the 24-mile-long Causeway has successfully weathered the test of time. Opened completely in 1969, it is the world’s longest continuous bridge over water and consists of north and southbound twin spans connected by seven emergency crossovers. Unfortunately, hurricanes Katrina in 2005 and Isaac in 2012 put the Causeway to the ultimate test, knocking out ramps leading to an electrical and communications deck below the southbound span near Crossover No. 5. After repairing the ramps for nearly $2 million, Causeway officials began looking for a more long-term remedy. It was inevitable that the ramps, at only 5 feet above the lake’s surface, would be torn apart again.

Robert Graham, operations director at the Greater New Orleans Expressway Commission in Metairie, says it made no sense to come back with the same configuration. “It would have been devastating to lose access to that equipment,” Graham says. “We’d have no call boxes if motorists became disabled, so we would have no way of knowing if anyone was broken down. It would affect us greatly.”

As a solution, the commission hired Boh Bros. to expand the crossover southward to accommodate the electrical vault and communication towers, thereby raising the equipment out of harm’s way.

Graham worked closely with Boh during the $8.2 million “9-Mile Turnaround Spans” project, while GEC, Inc. of Baton Rouge managed the contract under the guidance of Cary Bourgeois. Due to the nature of its purpose, the project qualified for Katrina emergency relief funding. “The site was not sustainable, so along with the Federal Highway Administration and Louisiana DOTD, we determined that the best long-term solution was to widen the crossover to support the equipment,” Bourgeois says.

On its surface, the project is straightforward: expand the existing crossover by nearly 9,500 square feet to support the relocated equipment. However, performing the work while keeping the heavily traveled Causeway fully operational required some innovative constructability input from Boh.

“It’s just a simple bridge span, a few lifts, a bunch of girders, and a concrete deck,” Bourgeois says. “The big story is where it’s located. The greatest challenge we have with all the work out there is dealing with traffic.” With that in mind, Boh devised a way to expand the crossover that would minimize the impact to the traveling public and accelerate the schedule, by capitalizing on the lessons it had learned on another recently completed Causeway project.

“It’s just a simple bridge span, a few lifts, a bunch of girders, and a concrete deck,” Bourgeois says. “The big story is where it’s located. The greatest challenge we have with all the work out there is dealing with traffic.” With that in mind, Boh devised a way to expand the crossover that would minimize the impact to the traveling public and accelerate the schedule, by capitalizing on the lessons it had learned on another recently completed Causeway project.

Boh project manager Thad Guidry says it was a matter of traffic engineering. “The original plan called for single lane closures on both sides to saw cut and remove the barrier rail, drive the piles and caps, and construct the new portion, all while working between the spans,” Guidry says. “As a value engineering alternative, we proposed moving the caps and piles closer to the middle between the two bridges to allow us to reach over the bridge to drive the piles.”

“We also opted to precast the pile caps in our New Orleans East yard and deliver them by barge, so they could be lifted and placed as well.” Chief Engineer Neil Hickok’s design team at Boh was instrumental in assisting with the re-design.

The design tweak also successfully addressed another concern: the ever-present windy conditions of Lake Pontchartrain. “Weather picks up pretty quickly on the lake, and we knew that working between the bridges could present an unsafe condition for our crews and the traveling public,” Guidry says. “Moving the bents a little closer gave us the clearance we needed for our piling leads and hammer to work from the outside.” Additionally, by constructing the caps in its New Orleans East yard Boh

significantly reduced the amount of time necessary for its crane to operate over the spans.

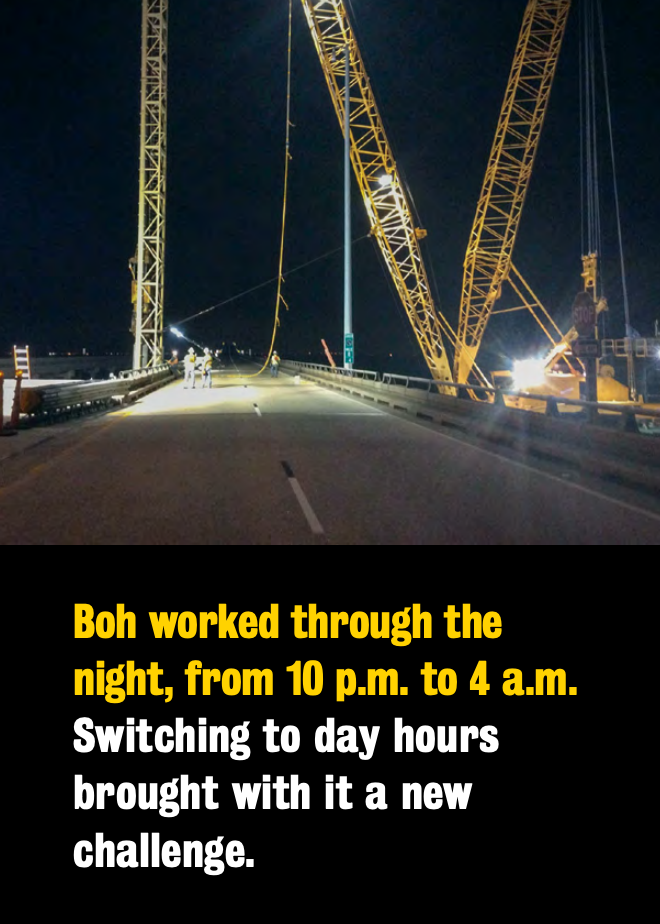

To make it happen, Boh worked through the night, from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m., and detoured traffic away from the span, depending upon which side the crew was working. “If we were driving the east piles and setting the east cap, we detoured northbound traffic to the southbound bridge at crossovers 6 and 4, and vice versa,” Guidry says. Through it all, minimizing the impact on traffic was essential. “We didn’t want traffic under us while we were reaching up and over the bridge.”

As foundation for the crossover expansion, Boh drove 26 100-foot-long, 36-inch-diameter concrete cylinder piles barged to the site by Gulf Coast Pre-Stress in Pass Christian, MS. Boh senior project manager Ron Brylski coordinated the pile driving effort. “It was an intricate operation in that we had to setup the template, stand up and drive the piles, and then move away from the bridge in the allotted time,” Brylski says. “We only had a five-hour window each night to do that.”

Given the logistical challenge of lifting and driving the large piles over the roadway, Boh used a Manitowoc 4100, 300-ton ringer crane equipped with a Vulcan hammer. “Driving the piles at that radius from the side of the bridge, as opposed to between the bridges, required a sizeable crane with tremendous lifting capacity,” Brylski adds. “Using this method allowed us to ensure safety while working and move our floating equipment the required one-mile distance from the bridge when we were not in a work period.”

Once pile driving was complete, Boh developed and submitted “as-built” pile locations and elevations to its New Orleans East yard to aid in the pre-casting of the caps. Rebar cages were cast into the six caps, intended to “shelve” into the piles, and temporary steel walkways were installed around the piles to aid in the caps’ placement.

As a next step, Boh placed 15 Type IV pre-stressed girders, also at night, then switched to daytime hours to perform the remainder of the deck construction. From there, crews worked from the existing crossover on the north side, using small equipment to install reinforcing steel, build forms, and place concrete for the expanded deck.

Daytime Traffic Toll

Switching to daylight hours brought with it a new challenge— getting equipment and material deliveries to the site under heavy traffic. As concrete trucks arrived, a police detail performed “rolling roadblocks” to provide access to the trucks while seeking to lessen the impact to the traveling public. Throughout the process, the Boh team could not block any of the emergency entries to the existing crossover.

Unquestionably, communication with the Causeway Commission was paramount. “We had to give the commission drawings of where we were going to have everything staged and where our lifting equipment was going to sit,” Guidry says. “On average, we were limited to less than half of the existing deck as working space.”

Traffic was detoured once more to lift and place a precast electrical vault structure that Boh had procured and barged to the site. Situated on the west side of the expanded crossover deck, the structure houses additional electrical equipment. A cell phone tower and other equipment for various telecommunications companies were also added to the expanded deck as part of a separate contract.

Completed in August and now operational, the expanded crossover provides a safe haven for the Causeway’s electrical and communications equipment, protecting it from the harm of rising waters caused by high winds, hurricanes, or tropical storms. Meanwhile, the existing crossover section remains in use for emergency vehicles and police.

Graham says the commission views the project as a vital step toward improving safety along the lengthy twin spans and is pleased with the success of the project. “Personally, I’m always happy when Boh wins our bid,” he adds. “They’re organized and prepared for any job they’ve ever done for us. They’re always professional and work safely. It just seems like they’re always equipped for anything that we have come up with. They’ve got the manpower and the equipment, and they mobilize quickly.”

Guidry attributes much of the project’s success in the field to the professionalism of Boh project superintendents Ricky Hogan and Tony McCallef, ringer foremen Mike Tregre and Mark Stevens, and operator Stanley Heinrich, Jr.

Recent Comments