The project to rehabilitate adjoining 100-year-old berths at the Port of Lake Charles was thrown a considerable curve ball when Hurricane Laura roared through the site during the pre-construction phase. Everything was put on hold for the better part of a year, as the damaged port focused on repairs to its infrastructure.

Fortunately, the project’s Construction Management at Risk (CMAR) contractual arrangement had already made great strides in building a collaborative team, which enabled them to swiftly pivot in the face of the escalating material prices and supply chain logjams that followed.

The current project is located within the port’s 200-acre City Docks General Cargo Facility, which moves some 500,000 tons of breakbulk cargo per year from 12 deepwater berths. Upon completion later this year, Boh Bros. will have replaced the timber substructures of the Berths 2 and 3 at the facility – measuring a combined 1,000 long by 150 feet wide – with concrete piles and a beefed-up 22 inch-thick concrete deck capable of handling heavier loads.

G.J. Schexnayder, Boh’s Vice President – Heavy Construction, says Boh played a critical early role in providing constructability, cost and schedule input throughout the preconstruction phase. When steel and concrete prices escalated, the CMAR arrangement allowed for the swift gathering and sharing of revised price quotes. “We’ve operated much like a partner,” Schexnayder says. “The team has been completely transparent throughout the process, brainstorming how to mitigate the price increases and providing constructability input to reduce some of the material quantities.”

Nick Pestello, Director of Engineering, Maintenance and Development at the port, says CMAR has undoubtedly been critical to the project’s success. As the owner’s representative and project manager, Pestello helped assemble the CMAR team. “We were able to bring in a contractor with real world construction experience early in the design process,” he adds. “Boh worked directly with the engineer, enabling us to price out different options as they came up.”

Boh brought several ideas to the table – along with the associated cost and schedule impacts of each – to help the team identify the best path forward. “We were always open to ideas,” Pestello says. “If anyone had a suggestion, we would all evaluate it and go through the process. That’s just something you can’t do in a traditional low bid scenario.”

Along the way, they realized cost savings, benefitted from lessons learned, developed methods for protecting adjacent facilities during construction, expedited the schedule and reduced risk.

Finding the Unexpected

The existing berths had been rehabilitated and repaired several times over the years, so “as-builts” were often incomplete and unreliable. Before work could begin, therefore, the Boh team had to perform exploratory work to find out what was there. “We spent the first couple of weeks mapping everything out,” says Thad Guidry, Boh Project Manager. “Conditions were quite different from what was assumed. The thickness of the deck, type and frequency of reinforcement etc. were different everywhere we looked.”

The Boh team worked the waterside area first – situated north of the bulkhead along the Calcasieu ship channel – first by removing the existing concrete deck then by cutting the existing creosote timber structure with chain saws at the water line and leaving the remainder of the structure in place. “Working from boats, we cut parts of the structure loose, rigged them up with a crane and ‘flew’ them onto land for processing,” Guidry says. “We then broke up all of the creosote with a track hoe and shipped the pieces out in about 250 dumpsters to an approved disposal site.”

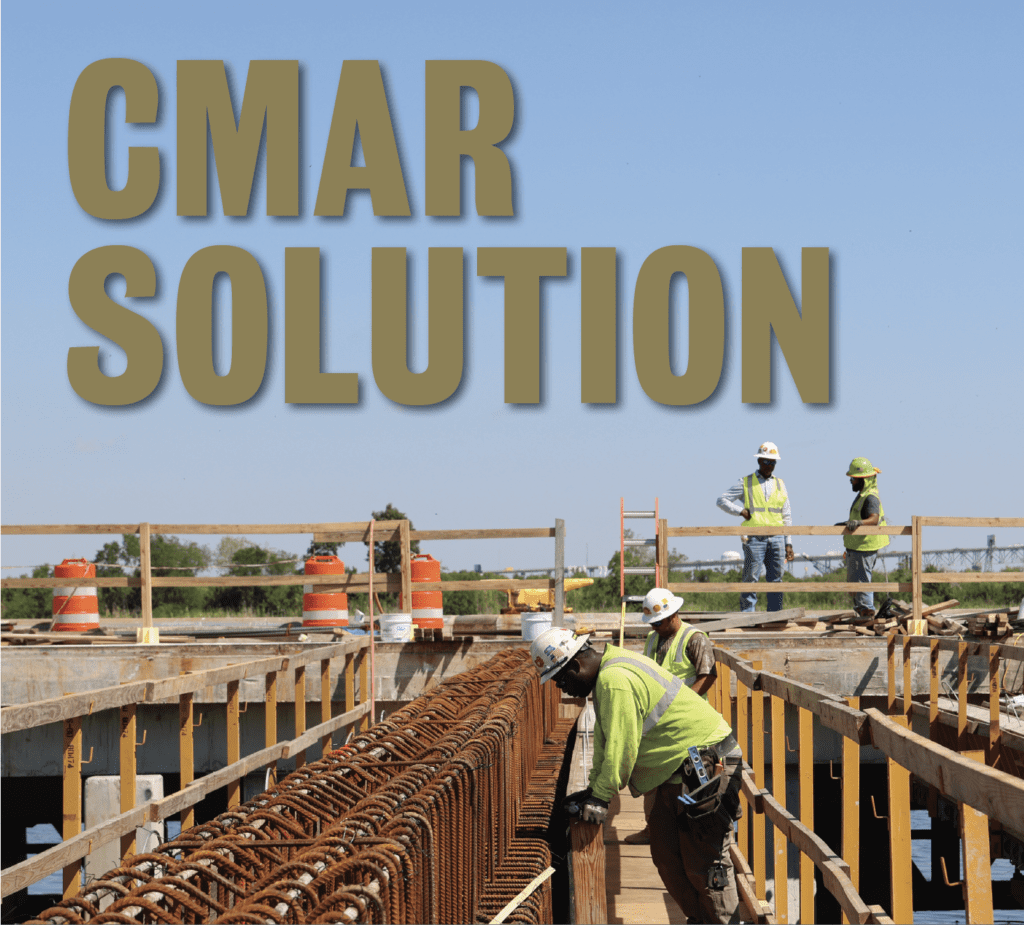

The crew then began pre-drilling and driving 24-inch-square, 105-foot-long PPC piles as foundational support for the new berths using a barge-mounted Manitowoc 4100 ringer crane. The waterside piles protrude about 14 feet above the water.

Then, turning their attention to the landside, Boh demolished holes in the existing pavement to make way for new concrete piles, using the existing pavement to support the crane. “By doing it that way, we didn’t need to disturb the site by backfilling or placing a lot of crane mats,” Guidry says. The Boh team ultimately drove 565 concrete piles and 15 pipe piles.

Once the landside piles had moved far enough along, Boh mobilized another crane and began waterside cast in place cap work. Later, they were spliced with the landside caps to make a single continuous cap. The 66 caps extend perpendicular to the river by some 150 feet, and measure 2-foot by 2-foot tall by 3.5 feet wide.

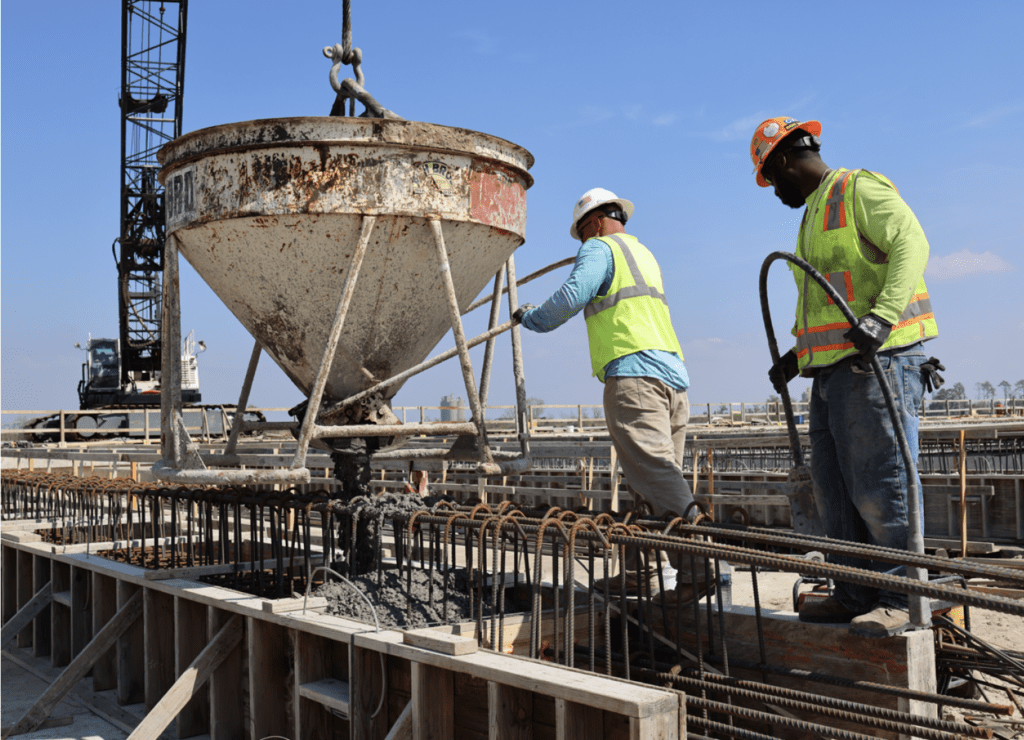

The Boh team then began placing concrete for the landside decks first, before turning their attention to the more complex waterside deck. While working waterside, the team placed 800 14-foot by 8-foot by 10-inch-thick precast panels (supplied by Waskey Bridge of Baton Rouge), in lieu of falsework, then followed with a 12 inch-thick topping slab. Upon completion, the berths will appear as one seamless deck.

Limited Real Estate and Other Challenges

Throughout the project, the site was surrounded by existing natural and man-made boundaries – Berth 1 to the east, Berth 3 apron and the ship channel to the west, railroad tracks to the south, and an existing 26-foot-wide apron to the north.

Essentially, the only access Boh had to maneuver equipment and materials was within the footprint of what they were building. That made scheduling deliveries and stockpiling materials particularly challenging. “There wasn’t much float to the schedule because of the access limitations,” Guidry says.

The limited access would frequently threaten the project’s timeline. For example, the Boh team would often need to cross the railroad tracks with materials or equipment. Each time, they would closely coordinate with the rail owners over schedules and build ramps down the sides of the track embankment with precast concrete or stone.

Tidal movements posed another threat – when the tide was high it was virtually impossible to perform demolition activities in the water. “The guys in the boat couldn’t maneuver the boats in high conditions,” says Tim Marks, Boh Superintendent. “But when we had a strong south wind, we knew the tides wouldn’t rise … those were the days we got the most done.”

Marks says the limited real estate represented a potential safety hazard, as well, particularly when operating heavy cranes and other equipment near water, power lines and railroad tracks. During demolition, for example, they ensured that workers were out of the swing radius of the crane as they lifted and placed demolished materials on the landside of the site.

Safety while working over the water was another concern. “We always desire for our workers to be in a safe environment, so we identified and communicated safety hazards before all phases,” Marks says. “At the start of each day, we’d have a 30-minute discussion with the foremen, and that would trickle down to the crews in their JSAs. Toolbox talks were also held each Tuesday, with safety topics specific to the job.”

Another challenge – the delays caused by Hurricane Laura at the project’s outset had significantly tightened the timeline. Nevertheless, Guidry says, the project was “blowing and going” in early summer. “We’re pouring concrete just about every day and will be for the next few months,” he says, adding that the project should be completed on time and within budget.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2023 Issue of the Boh Picture Magazine

Recent Comments