Silver lining

COVID-19 lockdown creates opportunity during I-310 rehab

Silver lining

COVID-19 lockdown creates opportunity during I-310 rehab

Maintaining a hurricane evacuation route is crucial, of course, but doing it during the tumultuous storm season of 2020 was a challenge due to the unusual number of storms requiring jobsite storm preparation and shutdown.

As Boh Bros. Construction Co. reconstructed a heavily-used 11.7-mile stretch of Interstate 310 from Interstate 10 to U.S. 90 in St. Charles Parish, the New Orleans area found itself in the projected cone of a hurricane some seven times and directly impacted at least once.

James Breland, operations manager in Boh’s Asphalt Group, says the original 30-year-old elevated and lower roadways needed a facelift, but storms and an early wet start relentlessly threatened to derail the project multiple times—especially near the project’s end as Hurricane Zeta scored a direct hit on New Orleans and knocked out power to the France Road asphalt plant.

![]()

Despite everything, Boh is set to finish the project ahead of schedule, successfully restoring failed concrete panels with PCCP in the existing mainline travel lanes and ramps, patching areas with full-depth asphalt, then overlaying portions of the mainline roadway as well as the shoulders for the entire stretch of the project with a new Superpave asphalt surface. Other work included new guardrail pads, guardrails to meet current state and federal safety standards in 55 locations, and 43 miles of striping on the existing mainline interstate and on/off ramps with high visibility, retro-reflective thermoplastic striping.

Despite everything, Boh is set to finish the project ahead of schedule, successfully restoring failed concrete panels with PCCP in the existing mainline travel lanes and ramps, patching areas with full-depth asphalt, then overlaying portions of the mainline roadway as well as the shoulders for the entire stretch of the project with a new Superpave asphalt surface. Other work included new guardrail pads, guardrails to meet current state and federal safety standards in 55 locations, and 43 miles of striping on the existing mainline interstate and on/off ramps with high visibility, retro-reflective thermoplastic striping.

Ironically, 2020’s other big calamity—the COVID-19 pandemic—created an opportunity for the Boh team to make up for lost time and even complete the work earlier. When the pandemic forced a lockdown and traffic counts dropped significantly, the team saw a chance to perform the concrete patching phase during the week instead of Winter 2020 BOH PICTURE 13 only on weekends as originally planned. They approached the DOTD project engineer with the idea and quickly received approval.

The decision was impactful, as Boh shrunk the overall timeframe for the concrete repairs. It was a clear win for the public and state. “Although the actual shifts to complete the work remained the same, we were able to reduce the overall schedule and give them the same quality product,” Breland says.

Getting it Done

After the Boh team scheduled, planned, and mapped out the project sequence early in the year, they began work in March by patching some 4,900 square yards of concrete panels. After closing lanes in 1,000- to 2,000-foot sections and detouring traffic with concrete barriers, the crew cut panels to full depth, removed existing concrete with a hydraulic hammer, drilled and dowelled into the existing concrete, and placed new concrete. After two days of curing, the lanes were re-opened to the public.

Stephen Alexander, a senior estimator in Boh’s Asphalt Group, says the patching operation was difficult, since “we weren’t in and out like with the asphalt paving. It was a multi-day process, and we had to break out the mainline roadway under traffic.”

“Once the barriers were up, we would saw cut the perimeter of the patch, use a hydraulic hammer to break it out, drill and dowel in the rebar, and pour the concrete back to the existing roadway—using the existing perimeter concrete as the forms,” he adds.

Work on the I-310 ramps was particularly under the gun, as the single-lane ramps had to be closed in their entirety and detour routes used to maintain public access. “We would have 10 hours on the mainline interstate, but only 8 or 9 hours for the ramps,” Alexander says. To facilitate the process, Boh’s team used a high-early strength concrete mix (which reaches 3,000 psi in 24 hours) so the lanes could open faster.

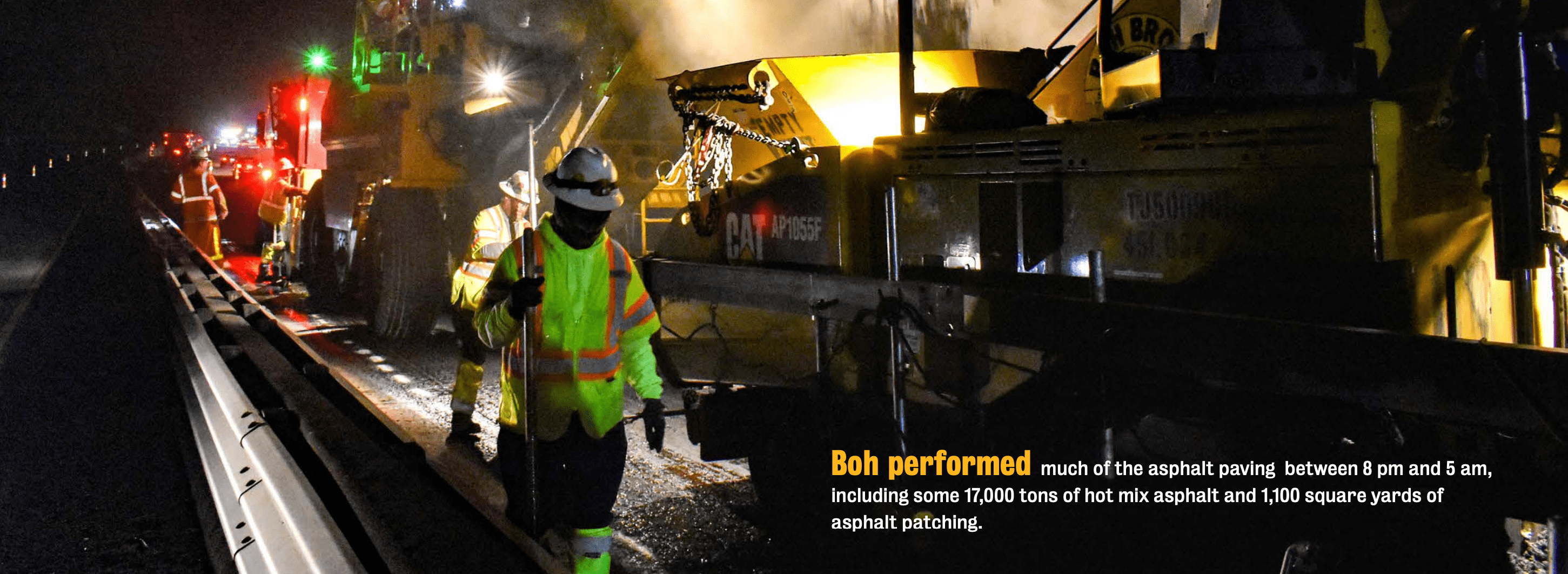

Boh performed much of the asphalt paving between 8 pm and 5 am, including some 17,000 tons of hot mix asphalt and 1,100 square yards of asphalt patching. A majority of the work called for a 2-inch cold plane and a 2-inch Level 2F Superpave asphalt overlay (a high friction course which is a state standard), with some 4-inch asphalt paving along the center cable barrier and at the new guardrail locations.

Boh produced the entirety of the asphalt at its France Road plant and relied on its CMEC-certified lab to ensure that the material met specifications. On-site, a QC technician ensured that quality was maintained as Boh’s paving crew laid the asphalt using a Caterpillar 1055F Series paver, Weiler material transfer vehicle, and compactors.

Keeping the team safe was paramount since Boh had to manage crews in multiple locations across the 11-mile site. “We were on a high-speed interstate, and while we wish the traveling public would slow down, that doesn’t always happen,” Breland says. “We made sure we had safe plans for our team members to work.”

Boh went way above and beyond the usual OSHA safety requirements—in addition to the OSHA-mandated Class 3 vests, the contractor provided crew members with reflective pants and LED hard hat lights to make them more visible. They also met with subcontractors beforehand to ensure that everyone was on the same page and maintained a police presence during every lane closure. In the field, there were daily safety meetings.

Communicating with the public was paramount, so Boh sent closure notifications to DOTD every week. Additionally, the contractor erected and maintained message boards at various locations.

It was helpful that Boh had long-standing relationships with many of its subcontractors. Two of the larger ones—Traffic Solutions LLC of New Orleans (signage, guard rails, closures) and Southern Synergy LLC of Laplace (striping)—played a significant role in the early project planning. “Communicating, getting everybody on the same page, putting a pre-plan together, and coordinating with those key subs was a big reason for the success of this project,” Breland says.

Hurricanes and a Pandemic

Like all projects in south Louisiana, the I-310 rehabilitation project was equally plagued by the COVID-19 pandemic and a bevy of hurricanes. The stretch of interstate is a critical hurricane evacuation route, so DOTD would mandate a shutdown several days before each landfall. Ultimately, the project was shut down as many as seven times as each storm threatened the region. “I’d get an email from the project engineer telling us no more lane closures until further notice,” project manager Kevin Bourgeois says. “Right away, we’d begin picking up message boards, signs on tripods, cones, etc., then put everything back out once the storm passed.”

Hurricane Zeta had the biggest impact, as it scored a near-direct hit on the New Orleans area and resulted in significant damage to the project signage. It was incredibly bad timing for the Boh crew. “We were actually milling the mainline interstate and had only milled one lane when we were forced to shut down,” Bourgeois says. “That left an uneven lane on the interstate, which was not the ideal situation.”

As an additional challenge, the France Road asphalt plant lost power after the hurricane for several days.

As an additional challenge, the France Road asphalt plant lost power after the hurricane for several days.

COVID-19, of course, brought its own unique challenges. Through it all, the Boh team found ways to alter work plans to allow for social distancing and added additional PPE such as masks or shields.

Boh also staggered its supervisor schedules and “went virtual” when possible to mitigate the possibility of COVID-19-related absences among project managers. “Management became a little more virtual at a time when the project had a lot going on,” Bourgeois adds. “We had to change some of our means and methods to make sure we kept our employees safe.”

Alexander says having the bulk of the management team at the France Road facility proved helpful in managing the various challenges. “From a day-to-day standpoint, if there was an issue or we had to discuss anything, it was a quick process,” he says. “I’m next door to the project manager, operations manager, and department manager, 50 feet away from our QC lab and not far from the actual asphalt plant. That makes it very easy to communicate and collaborate.”

A unique partnering relationship between Boh and DOTD proved particularly beneficial, as it facilitated a heightened level of communication and the quick resolution of issues. “We had input and they had input, and we worked to find common ground,” Alexander says.

This article was originally published in The Boh Picture. To read about more of Boh’s projects, click here.

Recent Comments