The lights went out nearly everywhere in New Orleans when Hurricane Ida tore through southeast Louisiana last August. The winds were blowing more than 150 mph as the storm brushed the city, damaging an Entergy tower along the Mississippi River at Avondale. In a matter of days, though, Entergy’s team of emergency electrical contractors had impressively and swiftly erected a temporary solution and restored power.

Nevertheless, they knew a more permanent fix would be needed. When the time came, the electrical provider chose to replace both the tower in Avondale as well as its sister tower on the other side of the river in Harahan. The solution came in the form of two new, more robust towers reaching over 400 feet tall and capable of withstanding hurricane-force winds.

Assisting the owner with the most economical design and schedule, Boh Bros. put together different pricing options for the tower’s foundations. “Within days, we began giving them budgetary pricing for several different pile types and configurations,” says Michael Lagasse, Boh’s project manager over the piling phase.

Once designs were finalized by Entergy and New Orleans-based Waldemar S. Nelson & Co. Inc. in December, the Boh team began ordering piles. And by early February, they had begun mobilizing equipment to begin work at the site.

The project ultimately required the construction of four concrete foundations at each tower site, one for each tower leg, that were each supported by 30 concrete piles. Additionally, four concrete strap beams linking the foundations are each supported by two piles. “Essentially, each tower leg gets a foundation,” he adds, “supported by 16-inch by 67-foot-long prestressed piles.” In all, Boh drove 124 piles on a 4-on-12 batter.

No Time to Spare

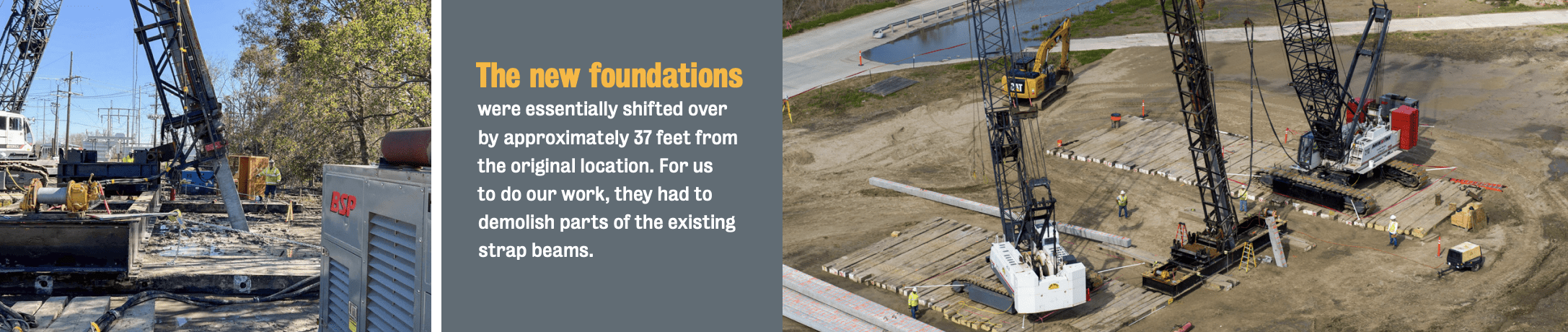

When Boh Bros. arrived at the site, another contractor had already removed the damaged Avondale tower and its associated foundations and was beginning a similar process at the Harahan site. The new foundations were similar to the existing foundations but shifted approximately 37 feet from the original location to avoid conflicts. In order to install the new foundations, the existing concrete strap beams needed to be demolished, but the original footings remained in place. The new design was similar to the existing design in that it contained four foundations connected by strap beams, but it was designed to be more robust than the original design.

Time was of the essence since all the work had to be completed while river levels were low and before the new towers arrived. “We were racing the river,” Lagasse says. “We had to drive the piles and place the concrete before the river levels came up. If the river caught us, we would have been shut down until the river levels decreased… and they needed to get this up for hurricane season.”

The Boh team mobilized a 200-ton driving rig with swing leads and a 110-ton assist rig and began driving piles within days. A custom-built 30-foot-long steel template with hydraulic winches, fabricated at Boh’s Almonaster facility, was used to help in guiding the battered piles.

The construction process was identical for both towers. The Boh team first drove the battered piles, then created underground strap beams to connect each of the four foundations. Next, they excavated to a depth of about 7 feet, then formed and placed the massive rebar-reinforced foundations using a combination of fabricated wood forms and EFCO forms.

The concrete mix design was conventional, but the foundations required exceedingly large anchor bolts as support for the towers. Precision was critical throughout the process. Significant design effort went into designing the anchor bolt templates and supports to ensure they did not shift during the concrete placement.

From there, the project was executed sequentially. The day Boh’s pile-driving crew finished work at the Avondale site, it began a similar process at the Harahan site as the civil crew took over at Avondale. Then, once the piles were driven at Harahan, the civil team moved over to finish the job. By June, the foundations were complete, the Avondale tower had been erected, and the erection of the Harahan tower had begun.

Everything moved quickly on the high-profile project. Boh’s multi-crew team worked 13 days on and one day off, and often 12 hours a day, to get it done. That still did not leave a lot of time to spare – the team installed the last strap beam just a few days before the first tower arrived.

An Eye on Safety

Leonard “L.P.” Parquet Jr., Boh’s site superintendent, says the demanding work schedule was easily the project’s biggest challenge but that everyone on the team shared a similar desire for the project to be completed as quickly and flawlessly as possible. “There were some long days and long hours,” Parquet says, “but it was necessary to expedite the work. We gave people some Sundays off when it was possible.”

Leonard “L.P.” Parquet Jr., Boh’s site superintendent, says the demanding work schedule was easily the project’s biggest challenge but that everyone on the team shared a similar desire for the project to be completed as quickly and flawlessly as possible. “There were some long days and long hours,” Parquet says, “but it was necessary to expedite the work. We gave people some Sundays off when it was possible.”

Parquet closely watched his team for signs of fatigue to ensure that safety and quality were not being compromised. Meetings were also held at the start of each day to go over tasks and high-risk areas, first with the foremen, then the entire project team. That was followed by breakout meetings between the foremen and their individual crews.

The entire process sometimes took over an hour. “These were lengthy discussions, but they paid off,” Parquet adds. “Staying aware of our surroundings and the dangers that we were facing was crucial on this job.”

Given the tight site and abundance of equipment, Parquet increased the number of designated spotters on site and flagged off the entire area. Boh site safety leaders Anthony Escobar and Earl Hano Jr. were also on hand to reinforce safety protocols. “If a worker had to enter the area, they had to get permission from the foreman,” Parquet says. “That way, we ensured that only approved personnel were in the area. We just did not have a lot of real estate to work with out there,” he adds.

“We hold ourselves to a very high standard for safety,” says safety representative Escobar. “Everyone worked as a team to create a safe project site.” Constant communication and a safe site meant crew members could focus on their tasks. “Without the support of the employees, foremen, and supervision, safety is nothing,” Escobar adds. “Our employees are the backbone of the entire operation.”

Through it all, the team worked collaboratively to complete the task at hand. Having the entire project team, from the Owner to the Contractor, with common goals resulted in a safe and successful job that finished on schedule.

Recent Comments